Smartphones are now ubiquitous—pocket-sized devices that combine telephony, computing, photography, internet access, navigation, and entertainment in a single sleek package. Yet it wasn’t until the early 1990s that the very first true “smartphone” emerged, bridging

the gap between mobile phone and personal digital assistant. To understand how we arrived at today’s capacitive-touch, multi-app ecosystems, we need to wind the clock back a few decades, examine the precursors, delve into the visionary device that kicked it all off, and trace the decades of evolution since.

Defining “Smartphone”

Before pinpointing when the first smartphone was made, it’s crucial to define what we mean by

“smartphone.” Early feature phones could make calls and send texts; PDAs (personal digital assistants) like the PalmPilot could manage calendars and contacts. A smartphone, however, integrates telephony with advanced computing capabilities: a touchscreen or keyboard, email and messaging, apps, and often a graphical interface. It merges the functionalities of a mobile phone, PDA, and more, running third-party applications. By this standard, simple mobile handsets of the 1980s and early PDAs fall short—they lacked true convergence.

Mobile Phones and PDAs: The Precursors

The first handheld mobile phone calls date back to 1973, when Martin Cooper of Motorola

demonstrated the DynaTAC prototype. Yet DynaTAC and its successors were purely voice devices, bulky and battery-hungry. Simultaneously, the world of PDAs flourished: devices like the Psion Organizer (1984) and the Apple Newton (1993) offered contact lists, simple apps, and handwriting recognition—but no voice capability. In Japan, companies like NTT DoCoMo began experimenting with data on mobile networks, introducing i-mode internet services in 1999. But none of these devices combined all key features into one.

IBM Simon: Birth of the First Smartphone

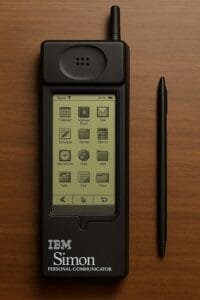

The true pioneer arrived in 1992, when IBM—partnering with BellSouth—conceived the “Simon Personal Communicator.” Designed by IBM engineer Frank Canova and his team, Simon blurred the lines between a mobile phone and a handheld computer. Development began in early 1992, and prototypes were showcased at trade shows later that year. Though bulky by today’s standards—roughly the size of a thick paperback novel and weighing nearly half a kilogram—Simon boasted a touchscreen, stylus input, address book, calendar, email, and even rudimentary fax capability.

From Concept to Reality: Development Time

IBM Simon debuted at BellSouth’s August 1994 launch, two years after its 1992 design approval, bringing together phone, PDA, fax, and email in one pioneering handheld.

line

After design approval in mid-1992, IBM and BellSouth engineers collaborated to refine hardware and

software. The touchscreen used simple monochrome graphics, and firmware ran on ROM chips. Early demos at COMDEX and the Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association (CTIA) garnered attention, with observers marveling at its integrated features. BellSouth officially launched Simon in August 1994, two years after its conception, marketing it as the world’s first “personal communicator.” It retailed for US $899 with a two-year service contract—a steep price that limited uptake.

Key Features of the IBM Simon

Simon’s groundbreaking features included:

– Touchscreen with Stylus: A 4.5-inch monochrome LCD supporting tap and drag gestures.

– Built-in Applications: Calendar, address book, world time clock, calculator, notepad, and email client.

– Fax and Pager Functions: Ability to send and receive faxes over cellular networks, plus text messaging and paging.

– Modular Expandability: An accessory port for third-party expansion modules.

– Battery: Lithium-ion pack offering roughly one hour of talk time or several hours of PDA use.

Despite its limitations—slow processor, limited memory (1 MB), monochrome display—it was revolutionary in combining these capabilities in one handheld unit.

Launch, Reception, and Shortcomings

When Simon hit the market in August 1994, reviews praised its concept but noted practical drawbacks. Its battery life allowed only about an hour of continuous talk, and stylus-based navigation could be finicky. The device’s weight (18 ounces) and the high price deterred mass adoption. Approximately 50,000 units sold before production ceased in 1995. Yet Simon’s legacy endured: it laid the blueprint for future devices, demonstrating consumer appetite for convergence.

Post-Simon Evolution: Ericsson R380 and Beyond

After Simon, the smartphone concept lay somewhat dormant until the late 1990s. In 2000, Ericsson introduced the R380, the first device branded “smartphone” by a manufacturer. Though it ran proprietary OS (EPOC), lacked third-party apps, and was still expensive, it featured a flip-cover revealing a touchscreen and offered email over GPRS networks. Meanwhile, Nokia’s Communicator series (beginning in 1996 with the Nokia 9000) merged phone and fax/modem with QWERTY keyboards, setting a different design path but still lacking the app ecosystems we know today.

The Rise of Mobile Operating Systems

The early 2000s saw the advent of true smartphone ecosystems. Research In Motion (RIM) launched

the BlackBerry 5810 in 2002, combining push-email and phone in a slim candy-bar form factor. Its secure enterprise email service made it a staple for business users. Palm, reborn from the Newton legacy, released the Treo series (2002 onward) with Palm OS, touchscreen, QWERTY keyboard, and third-party apps. Microsoft entered with Windows Mobile (Pocket PC 2000), porting desktop paradigms to handhelds. By mid-2000s, smartphones were defined by their OS ecosystems as much as hardware.

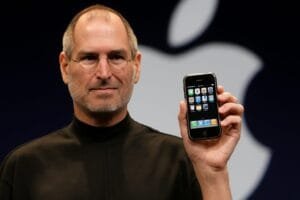

2007 and the iPhone Revolution

On January 9, 2007, Steve Jobs unveiled Apple’s iPhone—a device that synthesized the lessons of two decades of smartphone development. With capacitive multi-touch, a full-screen interface, mobile Safari browser, and the promise of third-party apps via the App Store (introduced in 2008), the iPhone reimagined user interaction. Though its launch units were 2G only and lacked features like copy-paste initially, it set new standards for hardware design, software integration, and carrier partnerships. By the end of 2007, the smartphone market shifted decisively toward touch-centric devices.

Android’s Emergence and the Open Era

Google responded with Android, an open-source mobile OS acquired in 20

05 and first released on the

HTC Dream (T-Mobile G1) in October 2008. Android brought a Linux kernel, Java-based app framework, and Google services integration. Its open-licensing attracted dozens of hardware partners (HTC, Samsung, Motorola), driving rapid innovation and price competition. By the early 2010s, Android smartphones outnumbered all others, offering choices from budget to flagship.

Smartphones Today: Ubiquity and Beyond

Fast forward to 2025: smartphones are indispensable tools worldwide. They feature multi-core processors rivaling laptops, high-resolution OLED displays, multi-lens cameras, biometric security (fingerprint, facial recognition), AI-powered assistants, and access to millions of apps across ecosystems. 5G connectivity, augmented reality, and foldable form factors push boundaries further. Yet it all traces back to the bold vision of IBM Simon in 1992—a handheld device combining voice and data, apps and telephony, that proved convergence was possible.

Why the First Smartphone Matters

The IBM Simon’s 1992 conception marked a turning point. It demonstrated that consumers would pay a premium for integrated communication and computing. It inspired engineers and entrepreneurs to explore new form factors, interfaces, and services. Even its shortcomings—bulk, limited battery, nascent touch interface—provided valuable lessons that shaped subsequent designs. Simon showed the power of rethinking a phone as a general computing platform, rather than a dedicated voice handset.

Lessons from Two Decades of Evolution

Looking back, several themes emerge:

1. Integration Over Specialization: Consumers gravitate toward fewer devices that do more.

2. Interface Matters: From stylus-driven monochrome to capacitive multi-touch, fluid interaction defines adoption.

3. Ecosystems Win: Third-party developers and app stores proved critical—IBM Simon pre-dated true app networks by years.

4. Battery and Connectivity: Advances in low-power chips and mobile networks (from analog to 5G) unlocked new use cases.

5. Design and Form Factor: Slimmer, lighter, and more ergonomic devices appealed broadly once technology allowed.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of IBM Simon

The narrative of the smartphone begins in earnest with the IBM Simon Personal Communicator, conceived in 1992 and launched two years later. Though commercially niche, Simon’s ambition—to unite telephony with computing in one handheld—sparked a revolution. Over the ensuing decades, innovations in hardware, software, and networks transformed that vision into the sleek, powerful devices we now rely on every day. As we look ahead—to foldables, wearable integration, and AI-driven experiences—we stand on the shoulders of that pioneering first smartphone, a testament to human ingenuity at the intersection of communication and computation.